Entangled lives: Shenzhen’s Urban Villages and the Chinese Anthropocene

This is Willa’s PhD proposal accepted by the University of Manchester’s SEED department in 2021. She explored Shenzhen’s urban villages as a lens into the Chinese Anthropocene. Philosophically grounded and methodologically rigorous, the research aimed to examine how these disappearing settlements reflect entangled forms of survival, inequality, and ecological transformation in a rapidly urbanising world.

Since the end of the last century, urban villages have been a primary ‘fort’ of affordable, convenient living. That above provide a sense of belonging for migrants from rural China in frontier cities like Shenzhen. However, due to the impact of urbanisation, the obsolescence of urban villages is not open for negotiation(Shenzhen Special Economic Zone News, 2005), as they are to be replaced by high-rise concrete blocks and skyscrapers.

My parents settled in Shenzhen in the 1980s and gave birth to me one decade later, which allowed me an unconscious but profound experience of the Chinese urbanisation which started at the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st century. My childhood and school life were accompanied by the sound of foundation percussion and concrete mixing. At that time, urban villages were very close to me and yet far away because these shabby and crowded spaces were frequently on my way to newly-built shopping malls, and offering cheap retail on daily necessities.

Having studied architecture in the UK, I learned from a Western perspective that the frenzy urban gentrification and construction I experienced since the start of the new millennium was at the expense of the environment. Compared to the Western style of modernisation in the 19th and 20th century, this East Asia’s temporally and volumetrically quite different development with the embedded massive population, and a rapidly increased production and consumption, is a decisive challenge in the epoch of Anthropocene we are facing in the 21st century, as argued from the lens of Western social sciences and humanities discourses(Horn and Bergthaller, 2020: 10, 172-175). Urban villages are acting as the temporary housing problem solver but waiting to be disposed, while migrants as the ‘powerless none-player in the contestation’ with the precariousness of being displaced(Hao, 2016).

In this thesis, I will offer a Chinese perspective on the Anthropocene through studying Shenzhen’s urban villages as an architectural and urban object which contribute to the survival of migrants in the context of a Chinese modernity. My five-year study in the UK offers me a unique experience, perception, and vision on the rise and fall of urban villages in the context of Shenzhen’s urbanisation, allowing an encounter of two ‘situated’ perspectives(Haraway, 1988), i.e., Western architectural/urban theories and Eastern Asian cultural background. The focus of my research is not to criticise state-capitalist urbanisation or the Chinese version of ‘dream of modernisation and progress’. Instead, my attitude aligns with that of anthropologist Anna Tsing, i.e., to study urban experience that bloom on the established and inescapable ‘ruins’(2015: 16-19). To ensure a successful implementation of this study depending on how the current pandemic situation in China or the UK might develop. The architectural, urban, sociological and anthropological approaches outlined below will be applied to my thesis either physically or virtually, according to a flexible and interchangeable methodology. The main research question is: How can urban villages, as lens, object, experience, inform future urban living/urban change in the Anthropocene, especially for developing countries?

Context and Literature Review

Eva Horn and Hannes Bergthaller believe China is central to the 21st centurial Anthropocene debate informed by two variants on Anthropocene’s causes and origins. One variant traced back to the earliest agricultural civilisation, while the other as the major, originated from the modernisation initiated by the West (2020). The reason behind is that from both, China has complex entanglements, opportunities and challenges to the global environment. Informed by the former, despite that the ideology of Anthropocene is an entirely Western thought, China in fact has a more extended and entangled historical experience in transforming the natural environment(e.g. wet-rice, Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal)(Horn and Bergthaller, 2020: 172). However, the early Chinese Dao’s philosophical emphasis on ‘the unity of man and nature’(天人合一) under the influence of the modern industrial revolution did not help to slow down the deforestation and species loss(Horn and Bergthaller, 2020: 174). Chinese scholar Hui Yuk explained that the seemingly exotic eastern philosophy could not intervene in the modern pecuniary world because these ideologies do not have thorough consideration on technological production. It is impossible to face a society that keeps evoking based on technological production/modernity, and even less to intervene or even make a change(2017). Informed by the latter, China leads to another acceleration to the environment in the 21st century following the West’s post-war urban restoration. After experiencing civil strife, epidemics, famine and humiliation by European military forces ended in the middle of the 20th century, China strives to return to its pre-modernity international political status. To prevent repeating the same mistakes, the central government spent almost one decade adjusting the development model to an eco-modernisation paradigm.[1] This “experimental” development model carries the ‘different [anthropocenic] responsibilities’ of the largest developing country embedded in the Paris Agreement(Nixon, 2017). That is, to explore a parallel development between economy and environment for other developing countries to follow in the anthropocenic epoch, whether successful or not(Horn and Bergthaller, 2020: 174). In 2018, the Chinese government designated the south-China city, Shenzhen, to be this eco-modernisation paradigm.[2]

Since 1978, Shenzhen has been designated by Xiaoping Deng as a “satellite city” of Hong Kong and the Special Economic Zone(SEZ) of China thanks to its superior trade-friendly harbour. Since then, its pivotal economic position in China attracted a massive influx of migrants, who have arrived in this cluster of fishing villages to seek jobs, especially in manufacture factory(Hao, 2016). The proliferation of the migrant population drives the demand for well-located but cheap rental housing. From two to three decades ago, the long-term institutional neglect and the citizen identification based (hukou 户口) housing policy, has led migrants to find accommodation disproportionately in urban villages and pay rent to the ‘indigenous villagers’(Y. Liu et al., 2018). Urban villages are the primary ‘fort’ of migrants, but facing demolition and gentrification in the government’s schedule as a geo-economic obstacle to modernisation. The two reasons that deem the obsolescence of urban villages by the government were: on the one hand, its current architecture condition cannot meet the modern building codes. On the other hand, the economic return of the urban-village land in the central city is not on par with the surrounding urban land occupied by high-rise buildings(Shenzhen Special Economic Zone News, 2005).

It was after the millennium when Chinese scholars began to draw attention to urban villages, the time those central-located urban villages in Shenzhen have already completed the ‘intensification’ in its unsustainable development pattern(Hao et al., 2011), reaching the spatial saturation. Before 2010, the topic of urban villages as informal low-rent clusters for migrants(Jiang et al., 2020) and its substandard daylight access, fire escape and hygienic condition in architecture (Hao, 2016) had been intensely studied and discussed in the discourses. Only a few mentioned the land value and the land-use transformation (Jiang et al., 2020). Due to the government’s dominance and the gradually ‘prejudice’ against urban villages’ existence in 2004, speculative activities and the formal market have turned their attention to these central urban villages. Therefore, gentrification and demolition were the topics concerned by scholars after 2010(Ibid.). Gradually in the 2010s, the demolition/gentrification of urban villages risked losing cheap labour forces for the Shenzhen’s economy(Lin et al., 2014; Lai and Tang, 2016). This economic concern brought out geological debates that the displacement issue of the inhabitants should be resolved through compensation and policies(Cheng et al. 2014; To and Tam, 2014). A trend followed it in sociology and anthropology focused on social exclusion and the heterogeneity of migrants in the late 2010s(Y. Liu et al., 2018; He and Wang, 2016).

The recognition of migrants in Chinese academia has changed from a mere economic development labour force to a marginalised heterogeneous group in the past two decades. However, as part of the research for my Master dissertation at Manchester School of Architecture, I studied how the Shenzhen Municipal Government has been promoting social housings in profoundly refined Chinese green building standards to succeed the environmental-friendly relocation and the wellbeing of migrants, to the peripheral Shenzhen. The reason behind is that the authority chooses to see the alienated value of urban villages under the capitalist anthropocenic environment(the concept of alienation brought out by Marx), but not its genuine value, i.e., the geographical and societal tolerance and inclusiveness for migrants. Rem Koolhaas believes that this modified landscape of single pursuit on form makes instant cities like Shenzhen disappear simultaneously as they become urbanised(Chattopadhyay, 2012: xv). The Shenzhen Municipal Government’s promotion on the green social housing seems to be a sound proof of Dipesh Chakrabarty’s argument that the capitalist political-economic knowledge toward ‘anthropogenic’ climate change regarding the responsibility of human beings, only worsen social injustice. It hides the heterogeneity behind the ‘Anthropo’; the rich and the poor(2017).

As a developing party-state-capitalist country with extremely hardcore targets for rapid eco-modernisation, to prevent the ‘metropolitan civilisation’ scenario of a ‘resourceful technological ingenuity’ articulated physical organisation and at the same time exacerbated more social problems in the dichotomy between the rich and the poor, displayed by the Western Industrial city in the 19th century, technological advancement is not the panacea of this anthropocenic crisis, even in this digital age(Chattopadhyay, 2012: xi-xii). Anna Tsing, American anthropologist, believes that the so-called pursuit of ‘progress’ on technology and economy is an ‘archaic’ characteristic of the 19th century(2015). By tracing wild-mushroom(matsutake) commerce, ecology, as well as the precarious/unstable livings of mushroom pickers, she claims types of survival strategies alienated from the capital/human society —— a cross-species entangled relationship between human, mushroom and pine. This kind of livelihood born from the mushroom’s capital chain but roles mutually support each other among species, not excavating and being excavated as the ordinary relationship between human and the other species in the Anthropocene. She further believes that this mode of survival may seem patchy, but rather a ‘third nature’ reveals the living despite capitalism.

The ‘third nature’ from my view is an anthropocenic indication for developed countries. The heterogeneity behind the ‘Anthropo’ includes the dichotomy of rich/poor simultaneously the dichotomy in developed/developing countries’ population. Shenzhen migrants choose to alienate themselves from their hometown and participate in this modern city’s capital production and “aspiration”, precariously accommodated in urban villages which is the only space they can afford to live in in the central city. Compared with mushroom pickers, they choose to be fastened in a narrow space, leaving themselves to be displaced in a pecuniary society and the planned demolition/gentrification of urban villages.

Note:

[1] China strives to reach the peak of carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. Thus, China increases its national eco-contribution by adopting more powerful policies and measures to continuously adjust and optimise the energy structure and industrial structure, seeking genuine economic growth(Xinhua Net, 2020).

[1]In 2018, Shenzhen was chosen as the pilot zone to implement the socialist demonstration area by the central government due to its advanced economic status and geographical advantage(Xinhua Net, 2019).

My hypothesis…

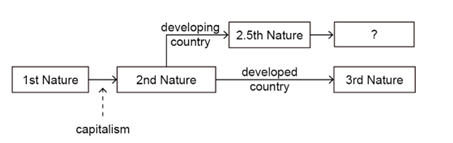

If the third nature is one step away from second nature to first nature, I will introduce the 2.5th nature, where Shenzhen migrants are, the instant of entering second nature(Fig 1). The threshold between the first and second nature produces precarious living, but the intrinsic qualities of 2.5th and third nature are entirely different. Suppose third nature offers an outward entangled living between human and nature. In that case, 2.5th nature has inward living entanglement to the second nature, while urban villages play a physical/spatial prerequisite. When Chinese migrants arrive in this megacity for any pecuniary purpose to work as a labour in this socialist economic production, the indigenous villagers provide low-cost rental houses with the best geographical location and city convenience. The received rents have also become the primary income of the indigenous villagers. Besides, citizens(such as me) regard urban villages as low-priced necessities and urban characteristics, which provide retailers (potentially run by migrants) in urban villages with consumption motivation. Among the three is a harmonious bottom-up pecuniary relationship that helps each other in the second nature. It is not as cross-species as the synergistic relationship between wild-mushrooms, pine trees and humans(Tsing, 2015), it crosses the living of social classes, a collaboration of diversity/difference, but in the established anthropocenic (socialist) capital environment. While the resistance to ‘making both humans and non-humans into resources for investment’ in the Western Anthropocene(Tsing, 2015), the Chinese Anthropocene is about the collision between the top-down eco-economic urban growth and bottom-up endeavoured lives to survive in; a story about those powerless migrants who constantly hone their survival skills in the rapid and overwhelming green urban sprawl and needs to be seen.

Figure 1 Introducing the 2.5th Nature (source: conduct by anthor)

Bibliography

Books

Abramson, D. M. (2016) Obsolescence: an architectural history. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press.

Architecture in the anthropocene : encounters among design, deep time, science and philosophy (2013). First edition., Ann Arbor: Open Humanities Press, an imprint of Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library (Open Access e-Books).

Chattopadhyay, S. (2012) Unlearning the city : infrastructure in a new optical field. Minneapolis: Univ of Minnesota Press.

Chakrabarty, D. (2017) ‘Anthropocene 1.’ In Szeman, I., Wenzel, J., and Yaeger, P. (eds) Fueling Culture. Fordham University Press (101 Words for Energy and Environment), pp. 39–42.

Cronon, W. (1991) ‘Pricing the Future.’ In Nature’s metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. London;New York; W. W. Norton, pp. 97–147.

Davis, H. and Turpin, E. (2015) Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies. Open Humanities Press.

Du, J. (2020) The Shenzhen experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City. Cambridge: MA: Harvard University Press.

Harvey, D. (1973) Social justice and the city. London: Edward Arnold.

Harvey, D. (1998) ‘What’s Green and Makes the Environment Go Round.’ In Jameson, F. and Miyoshi, M. (eds) The Culture of Globalisation. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 327–355.

Herrle, P. and Fokdal, J. (eds) (2014) Beyond Urbanism: Urban(Izing) Villages and the Mega-Urban Landscape in the Pearl River Delta in China: 20. Pap/DVD edition, Zürich: Lit Verlag.

Horn, E. and Bergthaller, H. (2020) The anthropocene: key issues for the humanities. London;New York, New York; Routledge.

Hui, Y. and Mackay, R. (2019) The Question Concerning Technology in China. Cambridge: Urbanomic.

Nixon, R. (2017) ‘Anthropocene 2.’ In Fueling Culture. Fordham University Press. pp. 43-46

Tsing, A. L. (2015) The mushroom at the end of the world: on the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Journal Articles

Chung, H. (2013) ‘The spatial dimension of negotiated power relations and social justice in the redevelopment of villages-in-the-city in China.’ Environment and Planning A. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England, 45(10) pp. 2459–2476.

Donna Haraway (1988) ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.’ Feminist studies. College Park, Md: Feminist Studies, Inc, 14(3) pp. 575–599.

Dou, P. and Chen, Y. (2017) ‘Dynamic monitoring of land-use/land-cover change and urban expansion in Shenzhen using Landsat imagery from 1988 to 2015.’ International Journal of Remote Sensing. Taylor & Francis, 38(19) pp. 5388–5407.

Fan, C. C. and Chen, C. (2013) ‘The new-generation migrant workers in China.’ In Rural Migrants in Urban China. Routledge, pp. 41–59.

Hao, P. (2016) ‘Urban Villages and the Contestation of Urban Space: The Case of Shenzhen.’ Mobility, Sociability and Well-Being of Urban Living, December, pp. 93–110.

Hao, P., Geertman, S., Hooimeijer, P. and Sliuzas, R. (2011) ‘Measuring the Development Patterns of Urban Villages in Shenzhen,’ April.

Hao, P., Geertman, S., Hooimeijer, P. and Sliuzas, R. (2012) ‘The Land-Use Diversity in Urban Villages in Shenzhen.’ Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. SAGE Publications Ltd, 44(11) pp. 2742–2764.

Hao, P., Geertman, S., Hooimeijer, P. and Sliuzas, R. (2013a) ‘Spatial Analyses of the Urban Village Development Process in Shenzhen, China.’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(6) pp. 2177–2197.

Hao, P., Hooimeijer, P., Sliuzas, R. and Geertman, S. (2013b) ‘What drives the spatial development of urban villages in China?’ Urban Studies. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England, 50(16) pp. 3394–3411.

He, S. and Wang, K. (2016) ‘China’s New Generation Migrant Workers’ Urban Experience and Well-Being.’ In Wang, D. and He, S. (eds) Mobility, Sociability and Well-being of Urban Living. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 67–91.

He, S., Kong, L. and Lin, G. (2016) ‘Interpreting China’s new urban spaces: state, market, and society in action.’ Urban Geography, 38, February, pp. 1– 8.

He, S. and Lin, G. C. (2015) ‘Producing and consuming China’s new urban space: State, market and society.’ Urban Studies. Sage Publications Sage UK: London, England, 52(15) pp. 2757–2773.

Hin, L. L. and Xin, L. (2011) ‘Redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen, China–An analysis of power relations and urban coalitions.’ Habitat International. Elsevier, 35(3) pp. 426–434.

Hochhäusl, S. and Lange, T. (2018) ‘Architecture and the Environment.’ Architectural histories. Ubiquity Press, Ltd, 6(1).

Jiang, Y., Mohabir, N., Ma, R., Wu, L. and Chen, M. (2020) ‘Whose village? Stakeholder interests in the urban renewal of Hubei old village in Shenzhen.’ Land Use Policy, 91, February, p. 104411.

Lai, Y. and Tang, B. (2016) ‘Institutional barriers to redevelopment of urban villages in China: A transaction cost perspective.’ Land Use Policy. Elsevier, 58 pp. 482–490.

Lin, Y., De Meulder, B. and Wang, S. (2011) ‘Understanding the ‘village in the city’in Guangzhou: Economic integration and development issue and their implications for the urban migrant.’ Urban Studies. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England, 48(16) pp. 3583–3598.

Lin, Y., De Meulder, B. and Wang, S. (2012) ‘The interplay of state, market and society in the socio-spatial transformation of “villages in the city” in Guangzhou.’ Environment and Urbanisation. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England, 24(1) pp. 325–343.

Lin, Y., Hao, P. and Geertman, S. (2015) ‘A conceptual framework on modes of governance for the regeneration of Chinese “villages in the city.”’ Urban Studies. Sage Publications Sage UK: London, England, 52(10) pp. 1774–1790.

Liu, Y., Geertman, S., Lin, Y. and Oort, F. van (2018) ‘Heterogeneity in displacement exposure of migrants in Shenzhen, China.’ Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(15) pp. 2562–2581.

Liu, C. (2010) ‘The characteristics of new-generation migrant workers and the challenges to citizenization.’ Population Research, 34(2) pp. 34–39.

Liu, Y., Li, Z. and Breitung, W. (2012) ‘The social networks of newgeneration migrants in China’s urbanised villages: A case study of Guangzhou.’ Habitat International, 36(1) pp. 192–200.

Ma, Y. (2019) ‘The Application of Harvey’s Theories into China’s Urbanisation of Capital.’

Malm, A. and Hornborg, A. (2014) ‘The geology of mankind? A critique of the Anthropocene narrative.’ The anthropocene review. London, England: SAGE Publications, 1(1) pp. 62–69.

Ortmann, S. and Thompson, M. R. (2014) ‘China’s obsession with Singapore: learning authoritarian modernity.’ The Pacific Review. Taylor & Francis, 27(3) pp. 433–455.

Wang, C. (2010) ‘Study on social integration of new generation migrant workers in cities.’ Population Research, 34(2) pp. 31–34.

Wang, M. Y. and Wu, J. (2010) ‘Migrant Workers in the Urban Labour Market of Shenzhen, China.’ Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. SAGE Publications Ltd, 42(6) pp. 1457–1475.

Wu, F., Zhang, F. and Webster, C. (2013) ‘Informality and the development and demolition of urban villages in the Chinese peri-urban area.’ Urban Studies. SAGE Publications Sage UK: London, England, 50(10) pp. 1919–1934.

Yang, K. and Ortmann, S. (2018) ‘From Sweden to Singapore: The Relevance of Foreign Models for China’s Rise.’ The China Quarterly. Cambridge University Press, 236, December, pp. 946–967.

Yeh, A. G.-O. and Wu, F. (1996) ‘The New Land Development Process and Urban Development in Chinese Cities*.’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 20(2) pp. 330–353.

Zhang, Xiao and Zhang, J. (2017) ‘MANAGING MIGRANT WORKERS AND URBAN SPATIAL PLANNING.’ Open House International. Open House International, 42(3) pp. 29–34.

Zhang, X. and Zhang, J. (2017) ‘Managing migrant workers and urban spatial planning.’ Open House International, 42, January, pp. 29–34.

Zhang, Y., Ruckelshaus, M., Arkema, K. K., Han, B., Lu, F., Zheng, H. and Ouyang, Z. (2020) ‘Synthetic vulnerability assessment to inform climate change adaptation along an urbanised coast of Shenzhen, China.’ Journal of Environmental Management, 255, February, p. 109915.

Zhu, Y. and Lin, L. (2014) ‘Continuity and change in the transition from the first to the second generation of migrants in China: Insights from a survey in Fujian.’ Habitat International, 42, April, pp. 147–154.

Newspapers

China News Weekly (2019) ‘Shenzhen baishizhou chaizhu chongjian chengzhongcun gaizao moshi yingfa guanzhu.’ (Shenzhen Baishizhou Demolition and Reconstruction The urban village reconstruction model has attracted attention). 917th ed. [Accessed on 11th May 2020] https://m.chinanews.com/wap/detail/zw/cj/2019/09-24/8964159.shtml.

People’s Daily (2004) ‘Urban Villages hamper development and progress thus must be redeveloped.’ People’s Daily. 26th October, p. A5.

Shenzhen Daily (2018) ‘Baishizhou naxie jiujiu de yingxiang.’ (Those old images of Baishizhou) Shenzhen Daily. Spring, p. A07.

Xinhua News Agency (2006) ‘Shenzhen chutai jianzhu jieneng fagui lizheng cong yuantou shang yizhi nenghao.’ (Shenzhen promulgates building energy conservation laws and strives to curb energy consumption from the source). The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of 89 China. [Accessed on 11th May 2020] http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2006- 11/01/content_430202.htm.

Xinhua Net (2018) ‘China to build Shenzhen into socialist demonstration area’ [Online] [Accessed on 2nd January 2021] http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-08/18/c_138318854.htm.

Xinhua Net (2020) ‘Jian Tan, Zhongguo Sheding Yinzhibiao.’ (Carbon reduction, China sets hard targets). [Online] [Accessed on 20th January 2021] http://www.xinhuanet.com/2020-09/30/c_1126560454.htm

Pan. YQ. (2017) ‘Baishizhou gaizao fangan gongshi! Wangzhaji 348 wan jiugai hangmu zhang shenmeyang?’ (Public announcement of Baishizhou renovation plan! What does the old bombing class of 3.48 million square meters of Wang bombing class look like?. China Daily. [Accessed on 11th May 2020] //sz.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201706/16/WS5be266dea3101a87ca9164b1.html.

Shenzhen Special Economic Zone News. (2005) ‘Weishenme Yao Gaizao Chengzhongcun’, (Why gentrifying Urban Villages). [Accessed on 3rd Jan 2021] http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2005-04-11/06555613089s.shtml

Websites

URBANUS (n.d.) Baishizhou 5 Villages Urban Regeneration Research, Shenzhen 2013. [Online] [Accessed on 11th May 2020a] http://www.urbanus.com.cn/projects/baishizhou/?lang=en.

Feng, E. (2018) Shenzhen’s largest ‘urban village’ thrives despite demolition orders. [Online] [Accessed on 16th April 2020] https://www.ft.com/content/c44936ba-5f2b-11e8-9334-2218e7146b04.

Research Network for Philosophy and Technology (2019) ‘Shenme Ren Fangwen Shenme Ren: Chaotuo Renleizhongxinzhuyi Kaituo Keji Xiangxiang - Zhuanfang Zhexuejia Xuyu’ (Who Visits Who: Beyond Anthropocentrism and Exploring Technological Imagination - Interview with Philosopher Yuk Hui). [Accessed on 3rd Jan 2021] http://philosophyandtechnology.network/2560/yuk-hui-interview-mingpao-cn/

Shenzhen Real Estate (2017) Public announcement of Baishizhou renovation plan! What does the oldest ‘’bombing class‘’ of 3.48 million square meters of king‘bombing class’ look like?(Baishizhou gaizao fangan gongshi! Wangzhaji 348 wan jiugai hangmu zhang shenmeyang?). [Online] [Accessed on 11th May 2020] https://sz.news.fang.com/open/25493842.html.